The Turkish Odyssey

I. Introduction

The conceptions of "Europeanness" and "Turkishness" are socially constructed identity labels. Although Turkey and Europe have been in close geographic and historical proximity, "Europeanness" and "Turkishness" have different connotations for foreign ideologies. From a post-Orientalist perspective, there is a Eurocentric tendency to identify Europeanness and Turkishness as "the Occident" and "the Oriental-other" respectively. Turkey's accession to the EU, or the project of officially incorporating Turkishness into Europeanness, underscored the concurrently growing salience of identity politics not only in the EU but also in Turkey. Since 1987, Turkey has been aspiring to become a full member of the EU. When Turkey's accession negotiations that aimed at implementing the laws of the EU were at their golden years in the 2000s, identity politics triggered different impulses in the European and Turkish political thoughts. The politicization of "Turkey as part of the EU" and simultaneous crackdowns in the Turkish liberal democracy led to the stigmatization of Turkey as "non-European". While the European public on average has become less enthusiastic for the enlargement of the union over the years, the European political elite has moved away from the politics of "Turkey in the EU" to the politics of "Turkey as a significant ally of the EU." Meanwhile, in Turkey, the rise of Justice and Development Party (AKP) and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan have endeavored to metamorphose the sociological and political chemistry of the country, arising societal polarization and authoritarianism, which eventually impeded the EU integration process.

To different extents, further yet exhausting integration and expansion of "Europeanness" in the region and Turkey's contemporary democratic-backsliding processes have fatigued the Turkish Odyssey: Turkey's journey for the accession to the EU.

II. Social Construction of European and Modern Turkish Identity

A. European Identity

Unraveling the progression of socially-constructed Europeanness rests on deciphering what the European identity stands for and what power mechanism constitutes this shared identity across the region.

Conceptually, identity has different connotations in the civic and cultural dimensions. In the context of Europe, the formation of Europeanness entails the construction of the "other" – the antithetical non-Europeanness (Mendez & Bachtler, 2016, p. 6). Unlike nation-state identities, the common identity of Europeanness lacks salient attributes of "a common language, cultural geography and territorial symbolism, historical memories, myths and traditions, religion, ethnicity or outsider groups" (Mendez & Bachtler, 2016, p. 6). Due to the absence of such shared elements, the European identity has predominantly relied on the presence of an "other" lacking overlapping civic and cultural Europeanness.

"A European 'civic identity' refers to the perception to be part of a European political system or even a 'European state' that defines rules, laws and rights with relevance for one's own life. A focus on the modern civic dimension would largely equate 'Europe' with 'European Union'. A European 'cultural identity' is independent from these political perceptions and labels the perception that fellow Europeans are closer than non-Europeans because of shared culture, values or history [...] Bruter (2004) finds that 'cultural' identifiers have to do with peace, harmony, the fading of historical divisions and co-operation between similar people and cultures, whereas the images of Europe held by 'civic' identifiers are related to the experience of open borders, mobility of citizens, common civic area, and economic prosperity" (Heinemann et al., 2020, p. 11).

Thereby, the definition of Europeanness and non-Europeanness have different interpretations across civic and cultural dimensions. As for the civic dimension, Europeanness implies social, political, and economic prosperity and welfare in the region, whereas non-Europeanness connotes the antithesis of such a meaning. As for the cultural dimension, Europeanness excludes culture, values or historical memory that are not shared in the region. Thus, civic and cultural dimensions emanate Europeanness that refers to a harmonious yet exclusive co-existence under the pillars of liberal democracy. As a socially constructed shared identity, Europeanness complements national and regional identities across the continental Europe. Thereby, the engineering of Europeanness sorts national and regional identities into those to be welcomed and those to be rejected.

Officially, the birth of this shared yet exclusive club of Europeanness dates back to 1973. At the Copenhagen Summit, the Heads of State briefly established a basis of European identity by emphasizing that the "the common heritage, interests and special obligations' are essential for Member States' foreign policy" (Heinemann et al., 2020, p. 9). Forming the grounds to foster a common Europeanness required the existence of an institutional authority. The increased salience of the EU and its institutions after the European Single Market program and Treaty reforms has established this needed decision-making authority. In light of this, European identity has been invented as the guarantor of the survival and further evolution of the political institutions of the EU (Heinemann et al., 2020, p. 9). Codifying provisions on EU citizenship, initiatives on European integration in the 1990s have delegated the institution of the EU the power to Europeanize the policies, polities and politics of Member States. Consequently, the EU project not only politicized European affairs in the national politics of Member States but also ended the "permissive consensus" of passive public approval for the EU among citizens, beginning "constraining dissensus" towards the EU integration process. Thus, after the politicization of the EU within national political discussions, national political parties have begun actively voicing criticisms regarding institutional competences and policies of the EU without rejecting the project of European integration (Toshkov et al., 2014, pp. 20-21).

Although the social construction of a shared Europeanness appears to be essentially ad hoc and ongoing today, the formation of supranational institutions within the EU demonstrates a success. Transferring notable decision-making power from national parliaments towards supranational institutions over time, the EU holds the capacity to shape and secure the project of Europeanness within Member States. In other words, the supranational institutions that cofunction under the EU hold the power to decide who is a member of the exclusive European identity and who is not.

B. Modern Turkish Identity

The emergence of modern Turkish identity dates back to the demise of the Ottoman Empire and the following nation-state formation led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Anatolian hills have a long history with parliamentary governments, dating back to the Ottoman Empire. Such a de-facto parliamentary tradition culminated in a de-jure parliamentary democracy in 1923. The establishment of the republic in 1923, followed by democratization and modernization efforts of Atatürk, emanated a Turkish identity focalized around modernism.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's Kemalist Reformation has pervaded the identity void left after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the 1920s and 1930s. It is known that Atatürk was heavily inspired by prominent intellectuals of the Enlightenment. Having six ideological principles such as republicanism, nationalism, secularism, statism, populism, and reformism, the Kemalist Reformation envisioned to bring the nation-state of Turkey to the level of the advanced states. The execution of this goal included strengthening the new central authority, facilitating nation-state building, secularizing Turkish state and society, fostering political participation, and conceiving changes in the socioeconomic structure of the country (Kili, 1980, p. 384). Unlike the emergence of European national identities after experiencing decades of Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, modern Turkishness manifested as a byproduct of Atatürk's concrete efforts to fasten Turkey's progress toward the social and economic values of the West (Kongar, 2016, pp. 240-243). Hence, Atatürk's perception of Westernization constitutes a socioeconomic modernization philosophy that is aware of the distinction between the best of the Western democracy on one hand and the exploitation of peoples propagated by Western ideologies like colonialism on the other. While stemming from ethnic roots, Atatürk's Turkishness is more than just an ethnicity as it corresponds to a model of citizenship. During this period Turkishness was a label adoptable by any individual willing to accept the terms of citizenship, legal and ideological, of the Turkish Republic. In the context of Turkey's independence and modernization maneuvers led by Atatürk, conformity with the ideals and goals of the Turkish republic is a necessary means to become part of modern Turkishness rather than a mere ethnic lineage. Therefore, modern Turkishness manifested in the late 1920s has been supra-ethnic on paper, which resembles the social construction of Europeanness.

In the post-Atatürk era of Turkey, the continuance of Kemalism has been certainly subjected to interpretation since it is an ideology that invites and harmonizes conflicting political positions from the right and left. Thereby, just as the nature of Kemalism was dynamic and organic, the interpretation of modern Turkishness by politicians also varied over the years after Atatürk. In spite of differences in the interpretation, modern Turkishness committed to secularism, positivism, rationalism, societal modernization, and public sovereignty angled the country and public towards Europeanization in the post-Atatürk era.

In the past decades, the politicization of the Turkish Odyssey for joining the EU has made the fracture between Europeanness and modern Turkishness visible, despite European and Turkish socio-political transformations.

III. Overview of Turkey-EU Relations

In the last 22 years, Turkey-EU relations have transformed tremendously. While Turkey's membership was debated in the region a decade ago, today let alone the possibility of membership, not a trace of cooperation seems to remain. For the scope of analysis, there are four critical phases, which identify and signify the changes in the sociopolitical trends for both Turkey and Europe.

1. Golden Years (1999-2006): Referred to as the Golden in academia, these years cover the prime vis-à-vis relations from the declaration of Turkey as a candidate for accession in the European Council in 1999 until the Turkish general elections of 2007. When the AKP rose to power in 2002, it took over the "EU anchor/wind" galvanized by the coalition governments in the 1990s, enacting and implementing new laws that conform to the EU bid (Soler, 2019, p. 4).

2. Peripeteia (2013): Like the peripeteia of the Greek tragedy, this interval marks Turkey's reversal of fortune in terms of the possibility of becoming a EU member after Turkey's incompatibility with the non-unified yet full member of the EU, Cyprus, and the reluctance of new conservative leaders in Germany and France (Soler, 2019, p. 5). Likewise, AKP had not been implementing the integration reforms since 2007. Peripeteia emerged during the Gezi Park protests in 2013, which arose as a reaction against the years of societal polarization and authoritarian revanchism instigated by the AKP. The protests mark the explicit manifestation of AKP's authoritarianism, denoting the backsliding of Turkey-EU relations.

3. Backslide (2016): This climactic juncture is identified with the utmost corrosion of liberal democracy in Turkey. Although the EU signed a Refugee Deal with Turkey, it continued to voice criticisms about Turkish policies in human rights, justice, and civil liberties (Soler, 2019, pp. 5-6). After the coup d'état attempt in 2016, following diplomatic crises and the constitutional referendum concerning the transition to the presidential system prompted Backslide. This solidified a paradigm shift in Turkey-EU relations from "a candidate" toward a "close partner."

4. Suspension (2019): Although the rifts among the EU and Turkey have been evident in the past, Suspension connotes the beginning of the quiescence of the negotiation process. In March 2019, the European Parliament voted to freeze the negotiation process as Member States had lost faith in the willingness of the AKP government to reform, legitimizing the downfall of the bilateral relations after 22 years (Soler, 2019, p. 6).

IV. Reactions Against the Accession Project of Turkish Identity into Europeanness

A. European Standpoint: Turkey as a partner, not a member

On the European side of the isle, the Turkish Odyssey for joining the EU has been a matter of concern for two actors: the political elites and the public. As the enlargement of the EU remains an abstraction that is not directly linked to people's daily lives, opinions concerning enlargement are widely constructed by the political elites. Thereby, when the question of Turkey has officially been on the table in the post-1999 period, also known as the Golden Years, clear-cut opinions on Turkish membership have emerged among the public. Growing salience of the "Turkish integration project into the EU" among the chambers of European political elites and wider public paradoxically impaired the perceptions towards Turkey. Such a predicament can be explained by the academic sentiment, "when there is controversy and polarization among political parties and elites with respect to certain issues, these issues become more salient among the wider public, and people tend to form clear-cut opinions on them" (Gerhards & Hans, 2011, p. 2). In other words, the salience of Turkishness as part of Europeanness has revealed all the cards of the European political actors on the table, which was not unanimously in favor of Turkey's accession.

European political elites like "the idea" of Turkey's accession, yet although this idea is charming enough to consider a strategic alliance, "the real" Turkey is not charming enough to be allowed into the club. Before Turkey's public image had deteriorated in terms of democratic-backsliding in the early 2010s, the political elite has begun pursuing a strategy towards Turkey that positioned the country "in the limbo between being an insider and an outsider," adding salt to the wound left by Turkey's multifaceted identity crisis (Aydintasbas, 2018, p. 2). Described as "hypocritical and dysfunctional" by the journalists and scholars, this strategy aimed to incorporate Turkey not as a full member but as "a strategically important partner that would make the EU stronger" by the 22 Member States (Aydintasbas, 2018, p. 4). Polarized debates among the political elites not only contributed to the establishment of this strategy into a status quo with regards to Turkey today, but also negatively impacted the wider European public attitude towards Turkey's integration to the EU.

The wider European public's attitudes towards Turkey's accession to the EU can be assessed by the factors of "the economic benefit of Turkey's EU membership, cultural differences, political ideology and citizens' generalized attitudes towards the EU" (Gerhards & Hans, 2011, p. 3). According to a study conducted by Gerhards and Hans, the more the citizens see the economic benefit of Turkish accession for their country, the less apparent or imagined cultural differences become. Similarly, the more positive view citizens have towards Europe and the EU in general, the more likely they are to support expanding the EU to include Turkey (2011). Thereby, the politicization of Turkey's integration has induced the saliency of Turkey's stigmatization as the "non-European" or "the Oriental-other" from a post-Orientalist reading, which coincided with the EU's "enlargement fatigue".

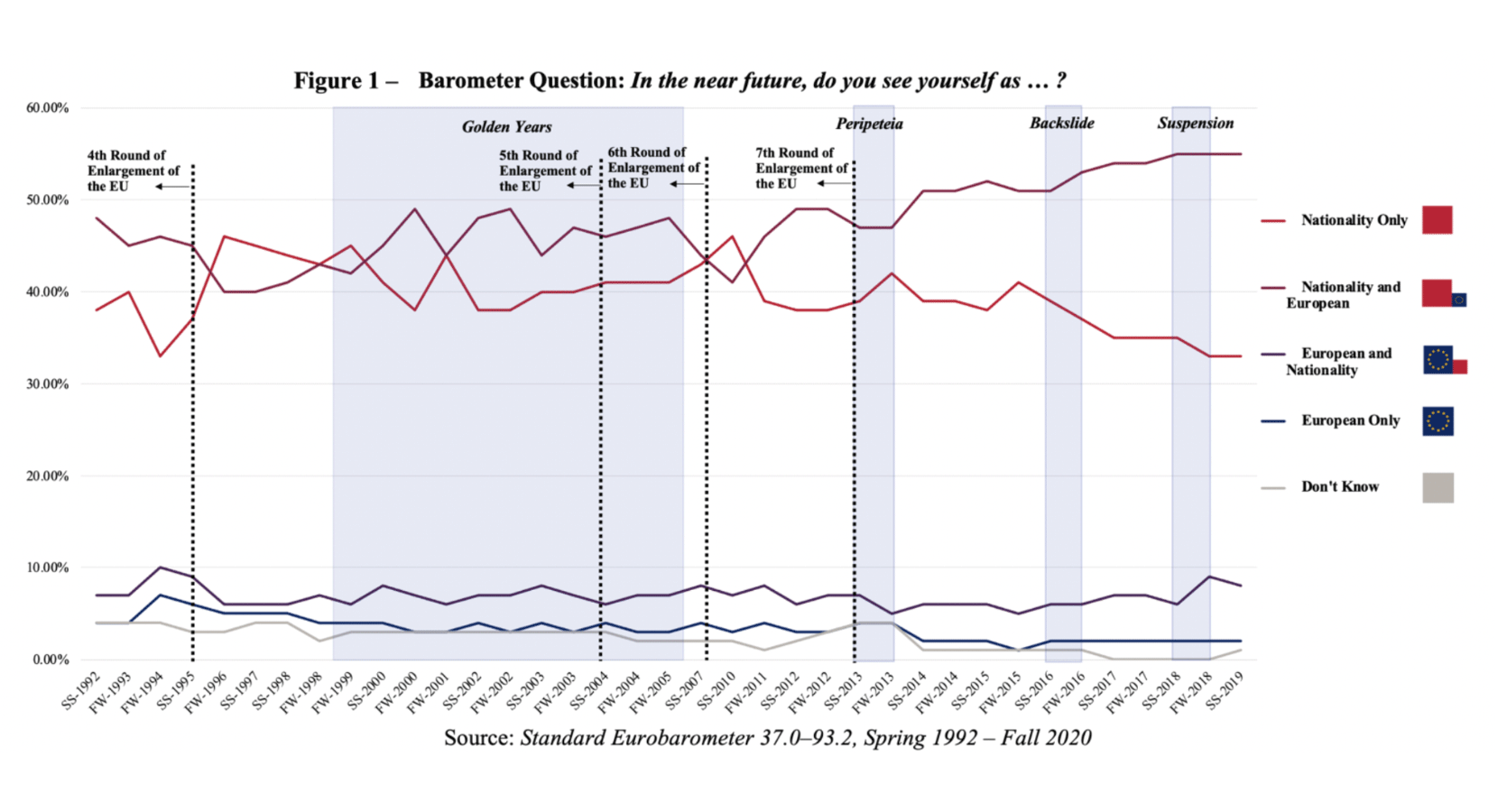

Unlike other candidate countries, the conventional encouragement of the socially engineered European identity stands as a barrier for Turkey. Demonstrating the historical progression of how citizens of the Member States identify themselves, Figure 1 displays that there is an increasing trend for the adoption of a dual identity, Nationality and Europeanness, over the years. During the Golden Years, the association with either a mono identity, Nationality Only, or a dual identity, Nationality and Europeanness seems to have fluctuated and become a concern that polarized the Member State citizens. Although the exogenous factors such as several rounds of enlargement of the EU, integration, and Brexit may have an impact on whether the Member State citizens identify themselves with a mono-nationalist identity or a dual-supranational identity, there appears to be a majority of citizens associated with the dual identity in the past couple of years. It appears that the majority of citizens are attracted to the socially constructed "Europeanness." By proliferating "Europeanness", the European political elites hindered the inclusion of the Turkish identity into the club of Europe.

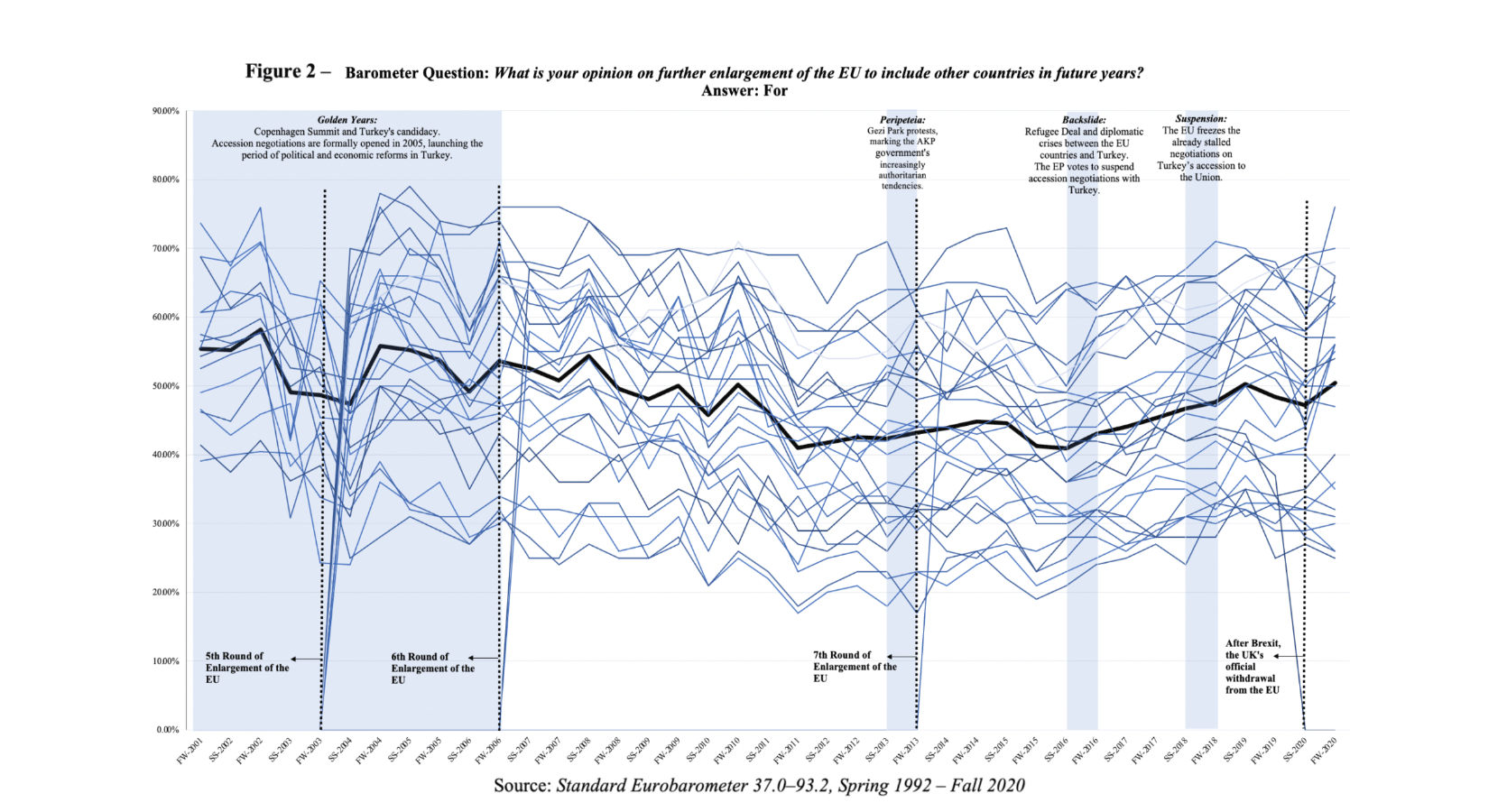

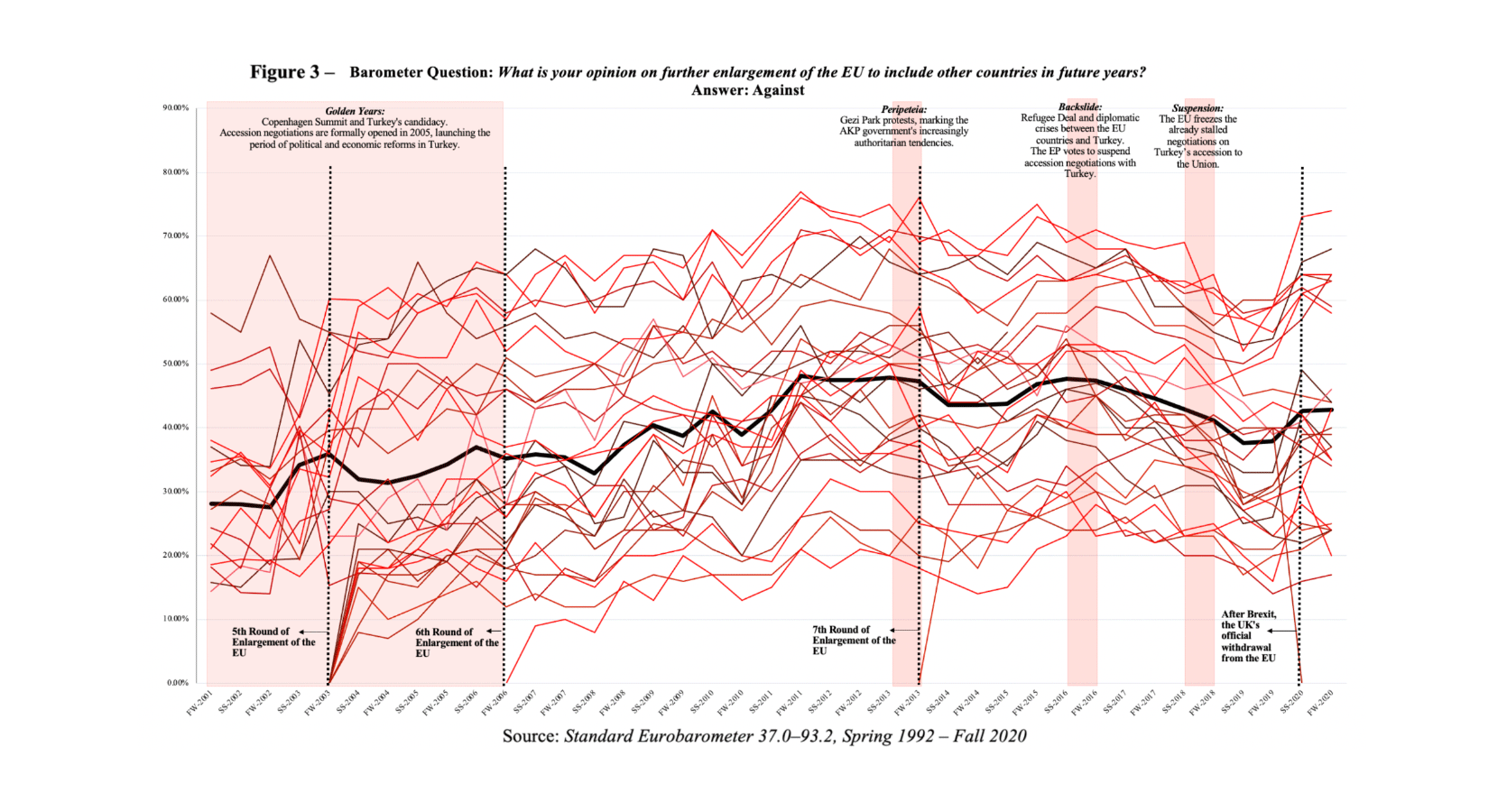

Visualizing the public opinion of the Member States regarding the enlargement of the EU, Figure 2 & 3 exhibit that after the Eastern European enlargement of the EU, the support for enlargement narrowed while the resistance to enlargement broadened. Although this phenomenon has reversed recently due to other exogenous socioeconomic and political factors, the "enlargement fatigue" seems to have exhausted the widening of Europeanness around the timeframe when Turkey has begun democratically-backsliding. These two figures highlight the concurrence of Turkey's already-present stigmatization as non-European and alienation from the socially constructed European identity. When the European public was trying to internalize and adapt into the EU's Eastern European enlargement, Turkey proceeded to a different direction of authoritarianism. The amalgamation and concurrence of both phenomena resulted in the European political elites to perceive Turkey as a "significant partner, not a member," leading to the growth of Turkish-skepticism among the European public.

During the Golden Years, the European political intelligentsia fueled the Pandora's box to be opened with regards to Turkey's integration to the EU, which was politicized after the failure of the Annan Plan in 2004 and the rise of Merkel in Germany and Sarkozy in France. The opening of this symbolic Pandora's box among the European public "revealed" distinctive hindrances, which cannot be explained by Turkey's democracy deficit, to fully adhere to Europeanness. On the other hand, Turkey's evident digression from the track of liberal democracy and the attempts to transform the modern Turkish identity by the AKP solidified the Eurocentric-Orientalist prospects in terms of Turkey's exclusion from the club. Thereby, the Turkish Odyssey for joining the EU is left halfway through, leading to Turkey's further isolation after the European discourse switched from "a full membership" to "a significant ally," and the AKP and Erdoğan intended to conceive a different image of Turkishness.

B. Surge of "New Turkey": U-turn on Turkish Democracy

On the Turkish side of the isle, their Odyssey was caught by the storm of Turkish-Islamic populism, entailing the erosion of liberal democracy within the country. Coming to power in 2002, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's AKP had aspired to prove itself as "conservative-democrats" to both Turkish seculars and the Western world, therefore the party and Erdoğan started propagandizing the discourse of "New Turkey." The fantasy of "New Turkey" brought the elimination of tutelages from "Old Turkey" and the fusion of powers concentrated at Erdoğan, inclining towards authoritarianism. Unlike "Old Turkey," which had been identified with Kemalism, "New Turkey" invented a metaphysical, neo-Ottoman myth for Turkey. This myth relied on the rhetoric by which the AKP "vilified the opposition, 'old elites,' and the existing political system, often by exaggerating and distorting the truth, if not by fabricating outright lies" (Somer, 2019, p. 56). Thus, "New Turkey" has become the embodiment of Erdoğan's Turkish-Islamic populist discourse, propagating the U-turn on liberal democracy.

In the early years of AKP and the last years of the "Old Turkey," the intelligentsia and AKP government heavily criticized and dissected Kemalism (Aytürk, 2022, pp. 23-51). The cleansing of Kemalism from government institutions by the authoritarian-revanchist attitudes of the AKP government harmed the democratic checks and balances of the country. Yet, the deconstruction of Kemalism was propagandized as a process of democratization with the EU anchor/wind in favor of the government, resulting in unchecked and corrupt AKP power in practice (Aytürk, 2022, pp. 23-51).

Thus, as the antithesis of Kemalism, the storm of Turkish-Islamic populism has become the cornerstone of the mythical "New Turkey." This right-wing populism subverted the principal-agent model theorized for liberal democracies, shrinking the capacity of the principal voters' ability to reward and punish the political agents and magnifying the roles of the president as the sole principal with no need of accountability and transparency in the democratic mechanisms. Erdoğan's rhetoric "had a chilling and Machiavellian undercurrent of politics understood as pure power, where 'the power and capacity to determine a friend and an enemy overlaps with the legitimate authority to establish a new legal order' à la Carl Schmitt" (Somer, 2019, p. 52). In light of this, the "New Turkey" had been a facade to legitimize the concentration of absolute power in one man, polarizing the country with right-wing authoritarianism and eroding liberal democracy. Thereby, the democratic notion of "Erdoğan for Turkey" metamorphosed to the illiberal-authoritarian perception of "Erdoğan is Turkey" within the ruling party AKP.

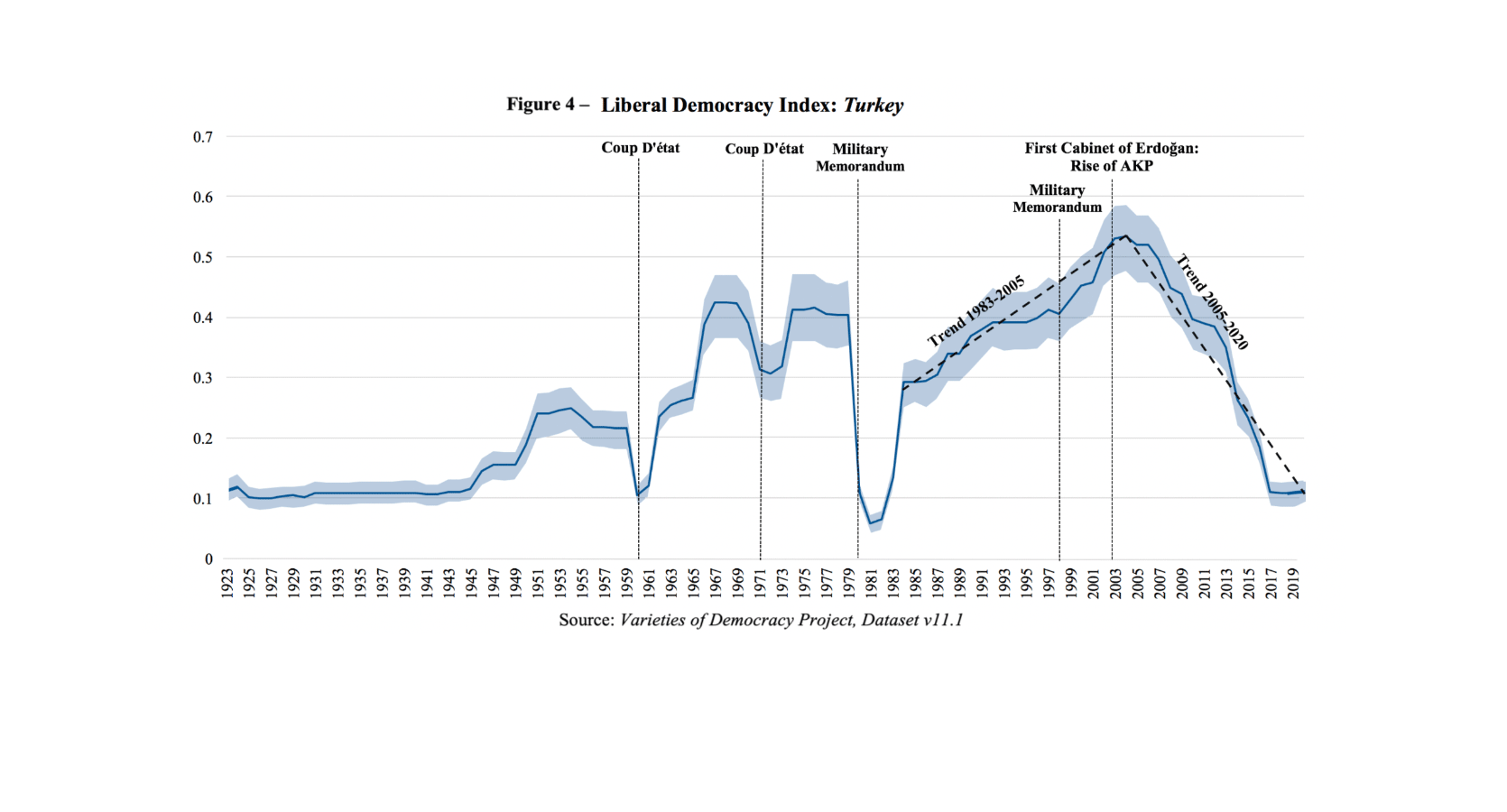

"Polarizing-cum-transformative politics and the dynamics of the resulting pernicious polarization" contributed to the AKP's and Turkey's authoritarian transformation (Somer, 2019, p. 55). Exploitation of such polarization and political dynamics emanated the AKP's and Erdoğan's right-wing populist discourse. This discourse of right-wing authoritarianism feeds from an "us-versus-them" rhetoric, which polarizes society and renders the country's liberal democracy track. Demarcating the historical trend of liberal democracy in Turkey, Figure 4 elucidates the deterioration of liberal democracy after the country was concretely intended to be entrenched with the authoritarian storm of Turkish-Islamic populism. Dropping recently to the liberal democracy index levels of the single-party period (1923-1946), Turkey has undergone a degradation in its civil liberties, accountability, and transparency as seen on Figure 4. Businesspeople, journalists, and opposition politicians have not only faced unlawful trials but also have been jailed. Indeed, Turkey has jailed the second-largest number of journalists (47) (Ozoglu, 2019). Such a profound demeaning in the civil liberties and freedom downgraded liberal democracy, disrupting the separation of the legislative, executive and judicial with an unchecked AKP power. Positioning himself as "the man of the nation" through his "charisma," Erdoğan's divisive rhetoric has helped him consolidate his power under a polarized nation. By framing the politics "as a battle between those defending their privileges in the "old Turkey" and those supporting a 'new Turkey,' similarly polarizing society in a trimodal fashion" (Somer, 2019, p. 53), Erdoğan managed to indoctrinate the idea that "Erdoğan is Turkey". The storm of right-wing Turkish-Islamic populism has challenged the modern Turkish identity constructed by Kemalism, thereby compelling the society to fracture, liberal values to languish, and institutions to decay. Growing authoritarianism in the country and rejection of the modern "Turkishness" committed to secularism, positivism, rationalism, societal modernization, and, especially, liberal democracy drifted the country away from integrating into the European identity, halting the EU bid.

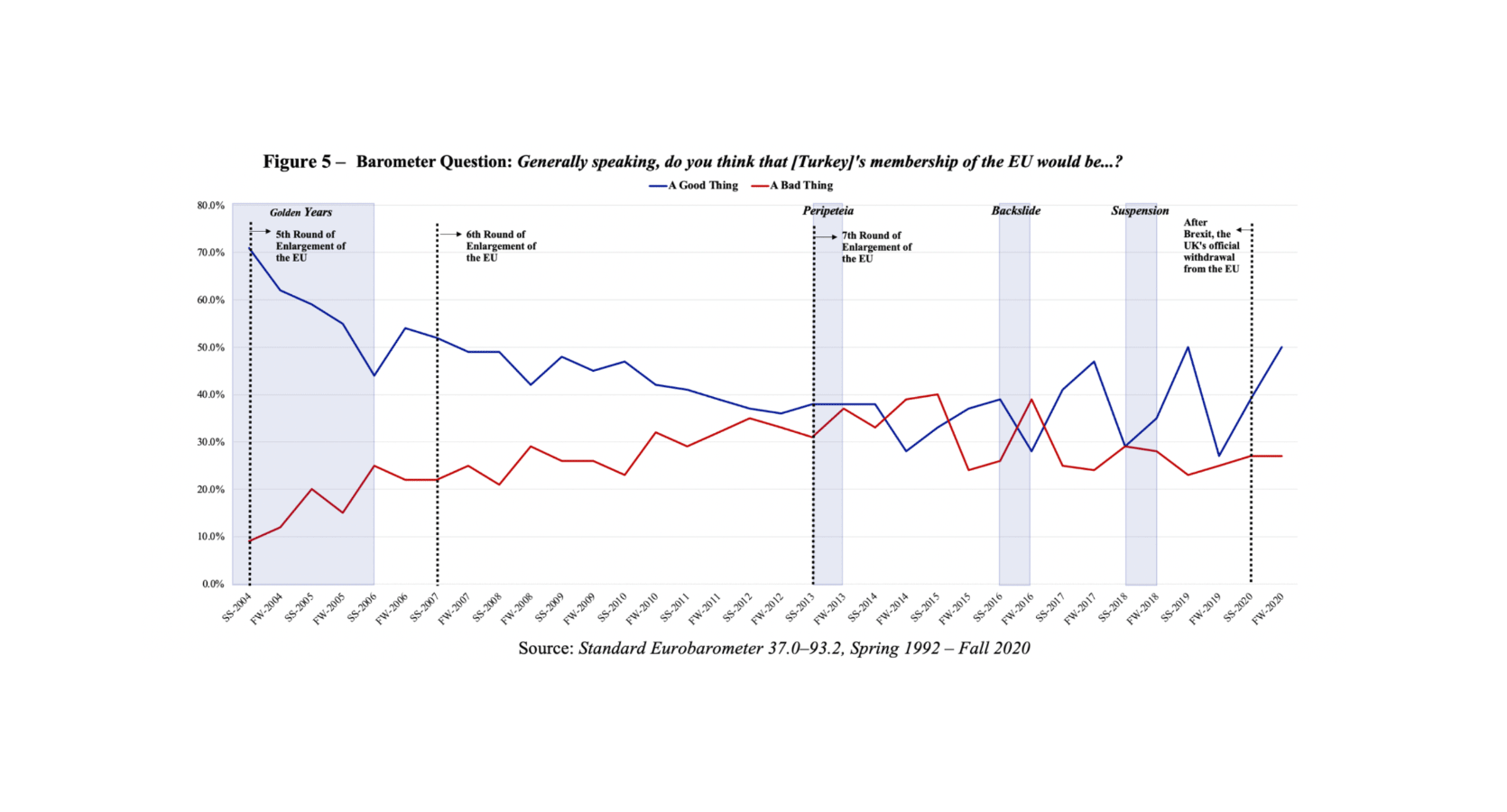

Evaluating Turkish citizens' opinion regarding Turkey's accession to the EU, Figure 5 points out the significant transformation of their thoughts over the years. As a result of the propagandization of "us-versus-them" rhetoric and its byproduct of Western-skepticism, the subject of integration became politicized. The subject of the EU accession, thus, became another domain for Turkish society to be polarized. The recent public opinion is close to a majority in support of EU membership, which may be explained by the hunger for liberal democracy and economic prosperity felt by the citizens and the exhausting societal polarization. The penetration of right-wing authoritarianism crumbled Turkey's liberal democracy track and, thus, altered the chemistry of the country, curbing the historically high public demand for EU membership.

V. Conclusion

Engineered "Europeanness" and modern-unitarian "Turkishness" may rationalize the setting and circumstances in which Turkey's accession process to the EU has been negotiated. Over recent decades, growing salience of Turkish membership and simultaneous downfall of the Turkish liberal democracy resulted in different reactions in the European and Turkish standing points.

The European answer to "Turkey in the EU" happened to be the confinement of Turkey in the political debates, evoking "perceived" barriers against Turkey's membership other than the country's democracy deficit. Despite the European public's slightly more negative attitudes towards Turkey, European political elites cast the country in limbo between being an insider and an outsider. Following Turkey's bruised liberal democracy, the European political elites and public seem to agree on associating Turkey with "non-Europeanness." This means that the political elite transformed their rhetoric regarding their relations with Turkey from "Turkey's membership to the EU" to "Turkey as a necessary ally/other".

Undoubtedly, Turkey mismanaged the candidacy process. The AKP and Erdoğan intended to transform the country both sociologically and politically, irritating fault lines among Ankara and various European capitals and undermining the historically achieved relations. The Turkish-Islamic populism has been polarizing Turkish society into camps, thus allowing the AKP and Erdoğan to consolidate their electoral base and power. Although Erdoğan came to power following the demand for democratization reforms and the EU anchor/wind that was storming the politics in the 2000s, his vision of "New Turkey" has renounced both liberal democratization and EU integration.

In the bigger picture concerning the EU enlargement, Turkey and the EU show signs of bilateral exhaustion as an aftermath of cross-cutting identity politics that have been predominant in the political discussions of the new millennia. Complementing and feeding each other, the Turkish skepticism intensified by Eurocentric-Orientalist attitudes and Western-skepticism nurtured by Erdoğan's Turkish-Islamic, mythic imagination for populism impede bilateral relations. To build momentum in Turkey's relations with Europe and ensure mutual cooperation in the future, both Turkey and the EU have to compromise and reconcile.

Therefore, the EU has to self-evaluate its mechanisms to dialogue its public and Ankara on matters of civil liberties. In return, Turkey must overcome democratic-backsliding by awakening from mythic abstractions. Ultimately, it takes two to cooperate, yet whether Turkey is going to take a step forward to further authoritarianism or to democratization is going to determine the future of the cooperation.

References

- Avrupa Birliği Katılım Müzakereleri. (2005). ab.gov.tr. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- Aydintasbas, A. (2018). The Discreet Charm of Hypocrisy: an EU-Turkey power audit. European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), 2-15. https://ecfr.eu/publication/the_ discreet_charm_of_hypocrisy_an_eu_turkey_power_audit/.

- Aytürk, İ. (2022). Post-Post-Kemalizm: Yeni Bir Paradigmayı Beklerken. In Post-Post-Kemalizm: Türkiye çalışmalarında Yeni Arayışlar (pp. 23–51). essay, İletişim.

- Coppedge, M. & Gerring, J. & Knutsen, H. & Lindberg, S. & Teorell, J. & Alizada, N. & Altman, D. & Bernhard, M. &Cornell, A. & Steven, M. & Gastaldi, L. & Gjerløw, H. & Glynn, A. & Hicken, A. & Hindle, G. & Ilchenko, N. & Krusell, J. & Luhrmann, A. & Maerz, S. & Marquardt, K. & McMann, K. & Mechkova, V. & Medzihorsky, J. & Paxton, P. & Pemstein, D. & Pernes, J. & Römer, J. & Seim, B. & Sigman, R. & Skaaning, S. & Staton, J. & Sundström, A. & Tzelgov, E. & Wang, Y. & Wig, T. & Wilson, S. & Ziblatt, D. (2021). V-Dem [Turkey–1923/Turkey–2020] Dataset v11.1. Varieties of Democracy Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds21.

- Kongar, E. (2016). 21. Yüzyılda Türkiye: 2000’li Yıllarda Türkiye’nin Toplumsal Yapısı. Remzi Kitabevi, 240-243, Print.

- European Commission. (1992-2020). Public opinion in the European Union. Standard Eurobarometer 37.0–93.2, Spring 1992 – Fall 2020.

- Gerhards, J., & Hans, S. (2011). Why not Turkey? attitudes towards Turkish membership in the EU among citizens in 27 European countries. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 49(4), 741–766. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2010.02155.x.

- Heinemann, F., Fuest, C., & Ciaglia, S. (2020). Fostering European Identity. European Integration Studies, 1(14), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.eis.1.14.25492.

- Kili, S. (1980). Kemalism in Contemporary Turkey. International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale de Science Politique, 1(3), 381–404. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1601123.

- Mendez, C. & Bachtler, J. (2016). European Identity and Citizen Attitudes to Cohesion Policy: What do we know?. COHESIFY Research Paper, 1(2), 4-12. http://www.cohesify.eu /downloads/Cohesify_Research_Paper1.pdf.

- Ozoglu, Melis. (2019). CPJ: Dunyada en az 250 gazeteci tutuklu, Cin ve Turkiye 'en buyuk gazeteci hapishanesi'. Euronews. Retrieved December 5, 2021, from https://tr.euronews. com/2019/12/11/cpj-dunyada-en-az-250-gazeteci-tutuklu-cin-ve-turkiye-en-buyuk-gazete ci-hapishanesi.

- Soler, E. (2019). EU-Turkey Relations: Mapping landmines and exploring alternative pathways. Foundation For European Progressive Studies: FEPS Policy Paper September 2019, 4-6. https://www.feps-europe.eu/downloads/publications/feps_eu_turkey_relations_soler.pdf.

- Somer, M. (2018). Turkey: The slippery slope from reformist to revolutionary polarization and Democratic breakdown. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 681(1), pp. 42–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218818056

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity Theory and Social Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/269587.

- The Failure of Turkey-EU Accession Talks Is Not All Turkey's Fault. (2019). mycountryeurope.com. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- Toshkov, D., Kortenska, E. K., Dimitrova, A., & Fagan, A. (2014). The ‘Old’ and the ‘New’ Europeans: Analyses of Public Opinion on EU Enlargement in Review. MAXCAP Working Paper Series, MAXCAP Working Paper Series, 2, 20–22. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from www.maxcap-project.eu.